Sabbatical Journal

In February and March of 2016 I fulfilled a long held dream of visiting South Asia. I spent three weeks volunteering at the Childhaven Home in Kathmandu, Nepal. Two of my journal entries are from that time. Childhaven operates seven homes for children in South Asia and I also visited several of the Childhaven homes in India. I spent a day touring one of the partner organizations of Childhaven, the Nepal Women’s Foundation which gives legal advocacy for women as well as operating its own school and providing employment for a number of women in cottage industries, including the production of low cost tampons.

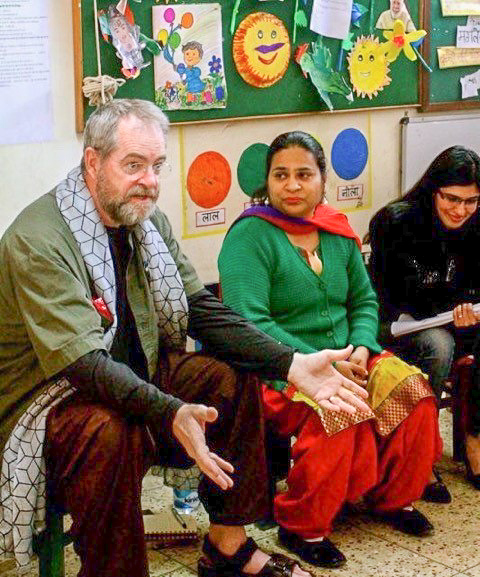

I gave a workshop on Storytelling at the Latika Vihar School in Dehradun, India and I have included a blog post from the school’s director in my journal.

I visited several projects of the Unitarian Service Committee of Canada which promotes sustainable agriculture through maintaining organic seed banks and working with farmer cooperatives. I visited farmer cooperatives in Bhadaure and Salvan, Nepal. (see journal entry: Unitarian Miracle)

I also toured the premier educational institution of Nepal, the Budhanikantha School, where the Unitarian Service Committee had sponsored a project of the School’s biodiversity club.

Since my return I have been a featured speaker at fundraising events for Childhaven International and The Women’s Foundation of Nepal.

Stories at Latika Vihar

By Jo Chopra

Stories have always been a big part of the daily round at the Latika Vihar School. We tell them in assembly, we read them out loud in the library and we encourage the children to share their own.

But John Marsh took it to another level in his storytelling workshop this week. He began by telling us what he called “a quiet story”.

But he soon progressed to a scary, action-packed version of the story-song: Abiyoyo.

The crowd loved it. Because we all know about scary monsters whose fingernails grow long and snarly and who refuse to brush their teeth – yet who are so small and insignificant they can be felled by a little girl with a ukulele.

John reminded us of the power of stories to transform our lives and of the importance we need to accord them if we are truly bring about change.

Thanks John

Childhaven Heroes

Don Fraser, rescuer of gods, kind of like Superman.

I have a new hero. His name is Don Fraser. He was my roommate at the Childhaven Home in Kathmandu, Nepal in February and March of this year (2016).

Like Superman’s alter ego, Clarke Kent, Don is mild mannered and soft-spoken. Underneath the mild exterior, however, lie bold ideals and convictions of steel. And like Superman himself, Don has a remarkable ability to do whatever it is that needs to be done: from editing a web page to shelling peas in the kitchen; from helping older boys prepare resumes and polish interview skills in the daytime to reading bedtime stories to younger boys at night: from tutoring two classes at the Green Tara School to supervising and participating in the cutting and splitting of wood for the kitchen fires.

This cutting and splitting of wood was critical last winter because the trade embargo imposed by India made propane a scarce commodity in Nepal. Wood from houses demolished in the recent earthquake, however, was plentiful. It was in the midst of this cutting and splitting that Don had occasion to rescue a god. Amidst the wood destined for burning, he discovered an ornate carving that was once part of a doorframe. (see picture)

In addition to all his regular duties, Don also found time to play a card game of whist with me most evenings as we wound down our day. It was during one of these games that Don told me that as much as he gives to Childhaven, he always gets more in return.

We volunteer at Childhaven in order to help children get a good start in life. In return we get back their smiles and affection, and the opportunity to make a real difference in their lives. We also get the opportunity to get to be part of a wonderful team of volunteers, with people like Don.

I am not claiming that Don is a saint. He snores like a lion with a bad cold. And while I would never accuse him of cheating at cards, he does seem to win more games than odds would allow.

So no, Don is not a saint, but he is a new hero of mine.

I showed Don an earlier version of this story. He was uncomfortable with the praise. He said the only thing part he recognized as himself was the snoring part. “Don,” I asked, “What is wrong with you? Do you want to live in a world where young people grow up wanting to be Donald Trump? You need to get over yourself.”

“Besides”, I confessed, “this story really isn’t about you, it’s about all of the volunteers here.” It’s true. Every volunteer I met at Childhaven gave me hope for the future of our world. They are all heroes to me. Their superpower is the depth of their compassion.

A Unitarian Miracle

2/24/2016

I was meeting with a group of farmers in the village of Bhadaure (population 400) in Nepal. Bhadaure is host to a school that also has a population of around 400, Many of the children travel from outlying villages to attend. It is located about an hour an half (28 relatively smooth kilometers and 6 wildly bumpy kilometers) east of Pokhara, one of Nepal’s larger cities and a popular tourist destination.

Farming is done cooperatively in Bhadaure. For the past twenty years it has benefited from the presence of NGOs (non government organizations) including the Unitarian Service Committee of Canada. That the President of the local cooperative, Tara Devi Gurung, should put a better way to get their excess organic produce to markets in Pokhara at the top of her list of needs is something like a Unitarian miracle.

Tell them we need a way to get our excess produce to market!

Pause to consider that Nepal has one of the lowest per capita incomes in the world (US $430 per year). The other category where Nepal ranks near the top is in government corruption. (Interestingly when it comes to least corruption, the Scandinavian countries all come out ahead of any in North America).

Bear in mind that the last twenty years have witnessed a massacre of Nepal’s royal family, a civil war, and a revolution. Prime ministers were sacked and replaced six times between 2000 and 2005. Then King Gyanendra dissolved the government amid a state of emergency, promising a return to democracy within three years. One year later mass demonstrations forced the King to act sooner. In 2008 the Maoist Communist party achieved a majority in parliament (one of the few communist governments ever to be elected in a democracy). It abolished the monarchy by a vote of 560 to 4, ending 240 years of royal rule. The Maoists themselves have had difficulty holding on to the reigns of power. There are currently 211 different political parties and coalitions rise and fall with astonishing speed. Then on 25 April 2015 Nepal suffered the worst earthquake in nearly a century.

The miracle is that through all this, the quality of life in the village of Bhadaure has steadily improved. How is this possible?

Some of it was luck. They were untouched by the earthquake of 2015. Some of it had to do with the district government being a lot more stable than the federal government. However, a lot of it had to do with assistance from NGOs. Twenty years ago most farmers were growing rice and wheat. They could subsist on it themselves and sell the rest. If there was a good harvest and they were able to get a good price for their crop, they could buy some fresh vegetables peddlers who traveled there with carts. Those peddlers don’t come any more. Bhadare is now teaming with fresh organic vegetables it produces itself, and is looking for a way to get its excess crops to Pokhara, where its vegetables are in high demand.

How did this happen?

Well, it was around 20 years ago that many NGO’s figured out that one of the best ways to make positive changes in developing societies is to educate the women. It is mostly women who are taking the leadership roles in the farming cooperatives. There have also been a host of other practical changes:

- Greenhouses made out of plastic add another two months to the growing season. The plastic will last seven years unless there are serious hail storms.

- The use of cattle urine as a fertilizer

- The use of home grown herbs as pesticides

- The creation of cooperative seed banks

- The appreciation of biodiversity

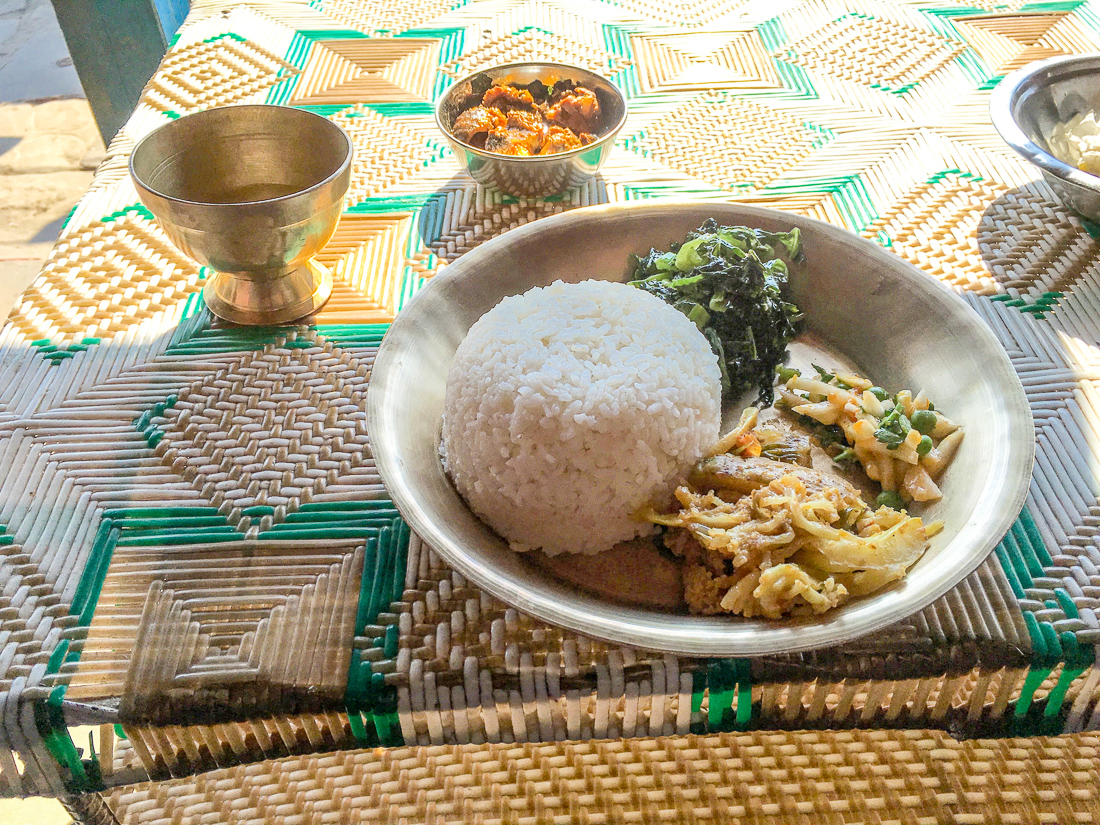

This last item is what adds the luster to this miracle. Where most farms in Nepal are still concentrating on one or two crops (Canola is now one of the big ones and cardamon is probably Nepal’s biggest export crop), the farms of Bhadare hold all that one could want in order to flourish: in the garden pictured here you can see: broad leaf mustard, peas, tomatoes, potatoes, pumpkins, garlic, sugar cane, radishes. We also saw coffee beans, ground apples (something like Jicama, but tastier), Brussels sprouts, broccoli, and cabbage and many whose names I did not know. Also on the farms were goats, chickens, Buffalo (the water kind), Oxen (the plow pulling kind), Cows (the milking kind) bees (the honey producing kind) and dogs (the alert you if there is a leopard near kind).

At one point in our meeting with the farmers I was asked why I would leave my comfortable home in Canada to visit this farm. My answer was that I felt something akin to the Buddha who chose to leave the comfort of his parent’s palace in order to understand reality. The Buddha was especially interested in understanding suffering. I never felt I had to travel to Nepal to experience suffering. However, the seventh principle of our Unitarian Universalist faith holds that our reality is bound together by an interconnected web of everything that exists. Nepal has helped me to appreciate that reality more deeply.

The Mirror that Couldn’t Hold Up

Kathmandu

My wife, Alison, can attest that I am comfortable amidst a high degree of grunge. She will also attest that I am occasionally possessed by urges to wash windows and scrub floors. One such mania overcame me this week.

My house mate volunteers and I at the Nepal Childhaven Home are collectively responsible for cleaning our own living space. The others here have all signed up for a longer tour of duty than me. Hence, they all have more responsibilities with the children. So I was happy to assign myself a day for cleaning.

The men’s bathroom screamed out for attention. Like many bathrooms in Nepal–it does not have a separate shower stall. You could think of it either as lacking a separate stall, or as being a large shower stall that includes a toilet and sink. It’s mostly tile and the acoustics are great.

The previous afternoon I made a pilgrimage to “Places”, a restaurant in Kathmandu famous for its excellent wifi connection. I was able to download the latest sermon pod-casts from the First Unitarian Congregation of Ottawa. A.J. Galazen’s sonorous tones reverberated off the tiles as I scrubbed away, listening to his magnificent sermon on the trials and opportunities of aging.

Above the sink was a glass shelf supported by a metal frame. I removed the shaving and teeth brushing implements. Removed the glass shelf, submerged it in soapy water, Scrubbed. Rinsed. Dried. Replaced. Easy Peasy!

The mirror above the shelf required more effort. I took it down. Sprayed, Polished. Repeated. Repeated. Repeated. Then repeated a few more times before I was satisfied that all that could be done, had been done. Carefully I reattached the mirror, checking that it was held firmly in place.

Then on to the windows and light fixtures in the common room. Twenty minutes later I was standing on a chair, reattaching a glass light fixture when there came a crashing explosion. My first thought was: World War III has stared! My second thought was: Earthquake! My third thought was: better check the bathroom.

It was a sorry sight. Shards of glass everywhere! The mirror had slipped its perch, smashed the glass shelf below, scattered toothbrushes and shaving creams, then tipped forward, shattered itself against the sink and finally fallen prostrate on the floor.

My mind whirled. I had checked the mirror’s firm attachment to the wall. I had re-checked it. The mirror had committed suicide. There was no other explanation.

This was my first opportunity to seriously go to work with a Nepali broom. They are made from a special plant, many strands bound together at one end, the other being a bit like an organic feather duster. It performed well.

I was determined that this was not going to be another do-good liberal effort that resulted in conditions being worse than the before the project commenced. The mirror had to be replaced. Another discovery. Mirrors are a bit of a specialty item in Nepal. They don’t sell them in hardware stores, nor in the kitchen shops that contain many household items beyond cooking utensils. I wondered about this because most Nepalese appear impeccably groomed. It’s not that mirrors are that rare here, but I wonder if the Nepalese check with siblings and spouses more and with mirrors less than most westerners. This was a bathroom for westerners however, and a replacement was found.

The other learning curve was getting rid of the glass shards. There is no municipal garbage collection. A lot of trash is Kathmandu is burned. A lot is simply dumped in the nearest vacant lot. Neither would do for the glass shards. The ever helpful paid staff told me that there was a weekly run of special trash to a medical college about a kilometre away. Problem solved. I did still feel bad about the old mirror. I pondered the cause. Perhaps it was the repeated spraying of ammonia in its face, or maybe it could not recognize itself amid clean surroundings. Many beings are resistant to change, even when common sense would dictate that the change is desirable.

Systems of Indenture

3/4/2016

In Kathmandu I said good-bye to two recent graduates of the Childhaven home. They were young men going to Dubai for two years. They would be working as semi-skilled laborers. There passports would be confiscated upon their arrival. They would not be allowed to find different employment in Dubai during these two years. They are basically indentured workers. Such practices are creeping into North America, but that is another story.

My coffee server at my Cdn. $25. per night hotel in Delhi (breakfast included) inquired where I was from. I gave my least complicated answer: “Canada.”

“A very fine Country!”

“Have you ever traveled outside India?”

The waiter shrugged his shoulders: “No, how could I?”

It was said without any resentment or anger directed at me, but I received it like a slap in the face from the universe: “Wake up to the reality in which you are immersed!” This waiter is your indentured servant.”

Gregory David Roberts, in his sometimes transcendent epic novel “Shantaram” berates tourists who haggle with their Indian hosts over prices. He admits that it is the “shrewd and amiable way to conduct your business in India”, however, the “little victories” haggled from” the hotel keeper cost that hotel keeper and his staff their daily bread and cost the tourists the opportunity to know them as human beings.

Of course, I was determined not to let this happen to me.

My first test happened when I employed a taxi driver to take me from Delhi’s Lotus Temple back to my hotel. I had the address written on a piece of paper. The driver did not seem to recognize the address and I told him it was near the airport.

“How much are you offering?”

I pointed, “We will use your meter.”

“The meter is broken.”

I was prepared for this. “Then you must name your price” He hesitated. I spoke again: “If you cannot name your price, I will find another taxi” (There was a line of them right behind us).

“400 Rupees”

“Fine.”

“First I will take you to a very fine shopping place.”

“No thank-you. No shopping today.”

“Yes, very fine shopping.”

“No, no shopping.”

“I know a hotel, better than the one you are staying — same price.”

“No, I want to go back to this hotel.”

“The airport is very far away, I must ask 500 rupees.”

Here was my test. I was certain the taxi driver would take me for 400 rupees. However, I had been dropped off at the Temple after visiting a Childhaven training site. I had no idea how long a ride it would be back to the hotel. I figured if it turned out to be a short ride, there would be no tip for the driver.

“Yes, 500 rupees, agreed.”

We drove about half a kilometer before my driver signaled a fellow cabbie, a younger man to pull over for a consult. My driver handed him the address and spoke in Hindi. I assumed he was checking directions.

However, the younger man then handed my driver 200 rupees and my driver instructed me to get in the younger man’s cab. “Same price” he assured. me. We were in a spot with lots of traffic and no line of taxis behind us. I had little choice.

I had been sold! The opportunity to get to know me as a human being had been haggled away for Cdn. $4.00.

The ride back to the hotel was a long one. I was tempted to give the young driver double the fare as a way of extracting revenge, but I settled on simply a generous tip.

E.M. Foerester in another novel, talks about the “rent we pay” for keeping our ideals about the goodness of humanity. My rent this day, was comparatively light.